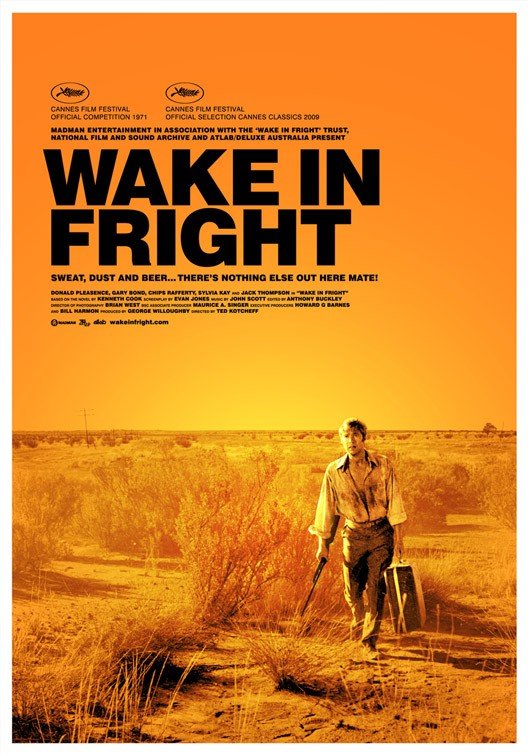

Wake in Fright, then go back to sleep before you remember what you did

dir: Ted Kotcheff

1971

Jeez, what a bunch of stinking flaming mongrels us Aussies were.

Wake in Fright in no uncertain terms establishes what a bunch of drunks and wasters populated the country before the quality children of the baby boomers came along and improved things immeasurably in the 80s and 90s.

Before that, well, fucking hell. Hell on earth both literally and figuratively. The place the wretched go in order to get their divine punishment.

I wanted to start this review by trying to argue that this isn’t really an Australian film anyway, but I feel like my argument ran out of steam before it started. I was going to argue that a film directed by a Canadian starring a British guy (Gary Bond) and co-starring another British guy (Donald Pleasance) was about as Australian as Madonna trying to do a Queensland accent, or Kylie Minogue trying to do a genteel English accent. But I can’t get past the fact that it’s based on a book written by an Australian author, being Kenneth Cook, who clearly saw how wretched the people of Broken Hill were back in the day. Certainly not now. I’m sure all Broken Hill’s residents are driving around in convertibles wearing monocles and top hats while smoking cigarettes out of fancy cigarette holders.

Or maybe it’s all meth and vaping these days, hard to know for sure.

This flick feels like it’s filmed on an alien planet, even to someone who’s been to these kinds of places, and been thrown out of those kinds of salt of the earth pubs, who’s never spent a cent on two-up or the pokies, but who’s drunk a fair few million pots of beer, and even, to my admitted shame, gone spotlighting and shot at the local fauna.

But even I watch this flick unable to believe what I’m watching, even as I’ve seen this kind of lifestyle firsthand.

The musical soundtrack is unsettling and like from either the weirdest western flick you’ve ever seen, or some science fiction flick pre-Star Wars, where people had antennas on their heads and lots of silver paint on their skins.

The first few minutes of screen time don’t involve drinking beer.

A school teacher, the only school teacher in a one-room school in a three building town, agonisingly waits for school to end, for the kids to fuck off, so he can set off out of this dusty hellhole back to civilisation (Sydney) for his Christmas holidays. But before he can do that, he has to drink beer at the pub, where he’s served by the surliest of barmen (John Meillon), who asks with a bark whether he’s got snakes in his pocket or not when he is slow to pay.

Every moment from then on involves drinking. I say this as a drinker myself; watching this amount of drinking is confronting and triggering, to use the vernacular of today. It’s almost like the author is implying drinking is a fundamental element/cancer of Australian society. It’s not just the rural places. It’s a countrywide disease.

It could be because of the ever present and oppressive heat. Every shot in this flick (except for some brief images of a woman cavorting in beach surf) makes you feel like you’re baking, stewing, basting in your own juices, and like you can barely keep your eyes open from the glare and the dust. And in the pubs, homes and shacks it’s barely any better, but at least you have cold beer, day or night.

The blue purity of the sky doesn’t make you feel like you’re in a wide open space. Somehow, these shots of the pervasive, unmitigated blue makes you feel like even the sky has it in for you. And if not you, then at least for John Grant (Gary Bond), the schoolteacher.

I thought for the longest time that the character was meant to be a Brit, but even though he’s played by a Brit, he’s just a stand-in for someone from the city forced to live in the country and teach. He calls it being a bonded slave to the Education department, in that he owes a bond equivalent to about $1000 which, until repaid, means he’s trapped in the boondocks indefinitely.

He looks down on the locals, any locals, all locals, mocks their simple ways, mocks even more their belief that there can be anything good about these desolate places. Of course he’s wrong, but the film knows that. His contempt, his Olympian disdain doesn’t mean he’s better than the people around him, it just means that he’s not good at hiding it.

The locals for their part don’t really care. This isn’t one of those stories where someone from the city rubs the locals the wrong way but is ultimately proven to be right with his Enlightenment principles and modern pedagogy. This is the flick where a city guy looks down on the locals, the locals rightly have little regard beyond contempt for him, and yet it is the city slicker, and not the locals, who drags himself down into the mud and destroys himself.

For all their faults it’s not the locals who force John Grant to fuck himself up. Sure, their aggressive friendliness, their dependence on any and all social transactions being transacted solely through beer is represented in a deranged and negative light, but they’re just being polite. They’re being nice. For most of the film, John doesn’t have to pay for any of the thousands of beers that he consumes, whether pots, schooners, cans or bottles. People are always willing to get him drinks, because they want to drink. No-one can bear drinking alone, but they will anyway if they have to.

Whatever self-control he may have possessed before, whatever aspirations to being any better than these local yokels, all that flies out of the fucking window after ten thousand drinks.

On his way to Sydney, he stops off in a fictional town the locals only refer to as The Yabba, but it’s really Broken Hill. Even under its patina of dust, if you’ve ever been to country towns, and never been to this one, you’ll recognise it. It looks like every fucking country town, only more so.

Naturally, John goes to a pub, since there’s nothing else to do until the morning, and it’s (after the closing time of 6.30pm, so it’s a lock-in), absolutely chockers with miners, farm workers and other reprobates. The local copper (screen legend Chips Rafferty, in his last film role) takes John under his wing, gives him the lay of the land, gently counsels him about how people go along in order to get along around here, but easily sees that this chap is going to hoist himself by his own petard.

John is introduced to the game of two-up, which so many of the men are betting on. How bizarre. I thought it was only played on Anzac Day, but what would I know? He derides it as a simple minded game for simple-minded fuckheads, but then manages to pin all his hopes and dreams on it, just like all these drunken losers.

But wait, he makes a few bets, and he’s up hundreds and hundreds of dollars! He’s on a roll!

Being the wise city-spawned sophisticate that he is, he knows when to fold ‘em, and when to walk away, and when to run, which he does with his winnings.

Back to his hotel room, he hugs the money, his eyes alight, he wonders “but what if I go back and bet it all again, then I could pay off the bond to the education department, and be free! Free! Free to get away from all these drunken hicks and row after row of their ugly, ugly children!”

I think even the least aware or experienced filmgoer can guess what happens next. Not only does he lose the money he won, he loses everything else. Everything.

When he wakes up the next day, he’s buck naked, and skint. By dint of the deposit he left for the key to his hotel room, he now has exactly 1 dollar. One of the old brown paper dollars we used to have.

There’s no way to get to Sydney anymore. There’s no way to do anything. Hell has no exits.

But you can still drink, somehow. John Grant’s downward spiral is only just beginning, because now, shaped by the place and the people he’s with, he has to both join them in their debauchery and forget that he ever thought he was above it.

There is so, so much in this flick, awfulness that happens, awful things that people do, and also a bunch of banal things, none of which seem that out of character for either the place or the era.

John ‘s downward spiral picks up another hitchhiker when he bumps into another aggressively friendly drunk who brings him home for more beers, and introduces him to his daughter Janette (played by English actress Sylvia Kay, who also happened to be the director’s wife), with whom John tries it on, and gets absolutely nowhere, only because he can’t perform, due to sheer drunkenness.

The pauses Janette takes before answering questions, and the thousand yard stare at the very least implies that she has seen a lot in her days. Though young, she is impressed by very little that men can do, and is impressed even less by John and his pretentions of either being an intellectual or somehow more worthy than the rest.

Two mates of her father’s come around as well, one of them played by another legend of Australian cinema, being Jack Thompson. He leers at Janette while plucking at his own chest-hair, acting like she should be intimidated or somehow aroused by him. She doesn’t seem to be. When Thompson’s character Dick wonders as to why John would rather talk to Janette, or any woman, for that matter, when there’s drinking to be done, he gets his answer about John being a schoolteacher, and that’s all the explanation he needs.

Maybe I shouldn’t read too much into it (but I can’t help it), but John’s lack of performance, the inability to go through with what he thought he wanted, punctuated with an occasion much later on when he possibly either is sexually assaulted, or engages in activities his sober self wouldn’t countenance, perhaps raises questions about John’s sexuality. Not that the actor’s sexuality has any role to play in any fair evaluation of the performance, or what it means in any fair analysis, but Gary Bond, who has since passed on - off of this mortal coil, lived his life happily out of the closet at a time when few others did so, so that makes me wonder (as to the director’s intentions, as opposed to the author’s).

The descent continues… On his further travels John ends up in the clutches of the good Doctor, being a truly depraved being played by Donald Pleasence. There is something inherently creepy about this character right from the start, and unlike the other people John crosses paths with, this one, Doc Clarence Tydon, this one is the only one who is openly malevolent.

Even as he generously shares his breakfast with John, or at least tries to. Who doesn’t want beer and kangaroo testicles for breakfast?

He, too, shares John’s contempt for the hicks in the sticks, but he doesn’t set himself as being above them. Oh no, no he’s not above them. He knows who and what he is, and revels both in that knowledge and the wallowing that he does. He’s an even bigger alcoholic than the rest of them, but he’s fine, as long as he just drinks beer.

If he drinks whisky, well, it’ll be on for young and old.

His comments, offered offhand, about Janette’s open sexuality, about her man-like propensity for selecting and discarding sexual partners is offered up almost as an anti-patriarchal corrective: why should she be condemned for behaviour celebrated in men by other men? But none of this has the positive effect we feel the Doc intends: the more words he speaks, with his unblinking lizard like eyes boring holes into John’s psyche, the more uncomfortable John gets. We know all he can think about is how he let himself down, how much he couldn’t perform, how much he doubts himself now.

But somehow Doc knows. I don’t know if it’s a great performance – I think his accent is distracting, falling in and out, so to speak, and doesn’t completely work unless you think of him as someone pretending to be an Aussie and pretending to be human. He is malevolence made flesh, and he will get have his pound of flesh from John, owed or not.

The lads. All the lads go boozing, at a tiny pub, and then go roo shooting. Scenes of kangaroos shooting ensue. It’s not faked, it’s not the magic of cinema, it’s not CGI. Just lots and lots of poor roos being slaughtered for real. The men are feral by now. They can’t just shoot the roos from a safe distance now, they have to kill them with their hands, with knives. Even though I could be thankful that those scenes involving the actors are faked. It’s still fucking horrible. John’s face, lit up with an idiotic lust to kill, spattered with blood; he is lost, but he doesn’t know how lost he is yet.

They return to the tiny pub, kick the door in for more service, and then, somehow, go even more insane, brawling, destroying the place, screaming mindlessly.

And yet there is worse to come.

Other viewers have a different opinion of what happens between Doc and John, and I’m not going to pretend that my view is correct or in any way better informed. Whatever it is that happened, and whatever it is that prompts John to eventually want to either kill Doc or himself or both, the images that swim in his mind sending him into a frenzy, are not images of Doc and John entwined in some kind of embrace or act, consensual or not; it’s images of Doc and Janette, of him either pleasing her or being cruel and sadistic, or both, that send him over the edge. But even then, is that a director implying something that couldn’t be shown in that era, or even possibly any era onscreen, as a somehow slightly more palatable alternative?

Where does the flick end? How do you end a shocking flick like this? Well, John tries to flee The Yabba, and ends up right back where he started, which is the worst fate of all, but at least he now seems resigned to his fate, knowing that it’s the fate he deserves.

This film is a blight upon Australia. It’s an indictment, a film-length accusation, a full-throated dare for anyone to contradict it. It is the last gasp of the “she’ll be right, mate” “the Lucky Country” mentality. It’s like watching the wholesale destruction of the Anglo-Saxon Australian colonial identity view of itself for thinking it had the remotest moral credibility, one which it never possessed.

I was never previously able to watch the whole film in one sitting previously, having tried a while back to watch it when it was screening one night on the SBS channel. I couldn’t do it. I just couldn’t do it. It was too bizarre, too raw, so fucking awful, so arch and so deranged.

But now I have watched it, and I am somewhat ragged and much the worse for wear, despite the print itself being an immaculately remastered version that looks more perfect than the day the original print was played to probably utterly baffled audiences back in 1971. It’s not my eyes that have been wearied, but my remnants of a soul.

Is Gary Bond’s performance a good one? Who knows? By dint of being a Pom, we’re already annoyed by him. But as an innocent who descends into the Inferno and improbably comes back alive, only to continue living in the Inferno, he is perfectly suited. There is a misplaced confidence (at first), as if he trusts he’ll always be able to make it through, and that things will surely never get too bad.

But they do, oh gods they do. There are horrors in this flick, and Grant either survives most of them or perpetrates some of them.

How he survives…I’ll never know. It’s stupid luck that sees him survive his lowest moments, almost like it’s a cosmic joke, like Australia isn’t done with him yet.

Everyone else, as in the Australians playing Australians, well, they’re pretty good at their task. So good in fact that I suspect the director’s directions to most of the actors was “Act in such a way that people around the world will be terrified of you.”

And, boy, did they read the assignment correctly. The whole production is amazing, and used for such evil purposes. It’s no wonder why no-one saw this back in the day, but now we treat it like it’s a cinema classic, which it is. Of course it’s a classic. Anytime any film maker sets something in the outback, and shows what arseholes Aussie men and women are, everyone has to genuflect at the altar of Wake in Fright, because it did all this, but fifty years ago.

The other element I can’t get over is that this same director, who is still somehow alive (he’s 92!), is the one who made, among other movies, Rambo: First Blood, Fun With Dick and Jane, and Weekend at Bernies.

This guy has seen and depicted humanity at its most mediocre and its absolute worst, the majority of the range of the human experience. He deserves a Nobel prize, though definitely not the Peace one.

9 times we should all stay the fuck away from Broken Hill (still) out of 10

--

“all the little devils are proud of hell” - Wake in Fright

- 213 reads