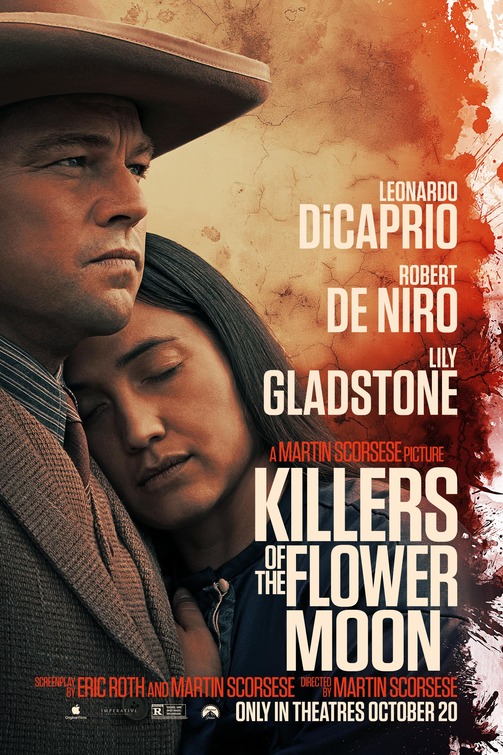

Hug each other tightly, because you don't know when

your uncle's gonna have you murdered

dir: Martin Scorsese

2023

Three and a half hours…

Everyone has better things to do than watch three and a half hour films in one sitting. I know some people watched this in cinemas originally, but, let’s be honest: Martin Scorsese himself wouldn’t be able to sit through this flick in one setting.

How do I know that? Well, if you’ve spent time with men in their 80s, or looked after a man in his 80s, you know there’s no way they’re sitting there for that long without needing help to the amenities at least 3 or four times.

And Scorsese, gods love him, is in his 80s. He has lost none of his abilities as a director telling big, complex stories in the widest, most maximalist ways possible, with the longest possible running times. Of course, this being a true story that focuses on a massive conspiracy of vicious jerks, committing so many crimes including and especially involving so many murders, it’s not unlike the films he’s most famous for, being his beloved mafia epics like Goodfellas, Casino and The Last Temptation of Christ.

You already know if you have the capacity for these late era Scorsese movies. A good bet is if you actually sat through the entirety of The Irishman without napping multiple times.

If so, you deserve a cookie, and you probably already watched this in a theatre. Good for you.

Based on the book of the same name by David Grann, this story is mostly set in the 1920s in Oklahoma. It is about a tribe, or at least a number of people from the Osage tribe, and a few others, who were forced to flee from Missouri to Oklahoma, put onto reservation land deemed worthless by the government, with the irony being that large oil deposits were later found there.

Due to the complex, byzantine legal arrangements controlling their lives (ie. structural racism) the tribal members have guardians, and are divided into competent and incompetent categories, having (white) ‘protectors’ guarding their money and doling it out as they see fit.

For all that, it’s the tribal folk who are dressed like they are whatever the 1920s equivalent of rockstars / pimps / celebrities must have been like, dripping with jewels and pricey fur coats and the like. It’s like watching early 1990s rap film clips. Shameless displays of wealth, with the Osage buying the fancy cars and making it rain at the strip clubs.

Shameful behavior. And yet they’re not even, in a lot of instances, in charge of their own money.

Despite the fact that, um, for hundreds of years AFTER the revolution that separated America from the Empire, and even many decades after the end of slavery and the Civil War, the indigenous weren’t really considered to be fully human, or to be worthy of self-determination. Savages, I think is the common phrase used to describe them by the (white) people that strangely seem to surround them.

It is a bit weird, isn’t it, that all these white people are hanging around these tribal folks, at the same time thinking that they’re degenerate sub-humans that deserve to be annihilated? And it’s really weird that all these (white) men really, really want to marry these and any available Osage women?

Well, let’s be more specific: they are marrying into specific Osage families with control of certain lands where oil just happens to have been found in abundance.

And wouldn’t you know it – many of these Osage women and their relatives just start randomly dying / being murdered?

Through such troubling times it’s a comfort, a real comfort and boon to these poor (rich, indigenous) folks that they have a (white) ally on their side, someone looking out for their interests, in the form of true philanthropist William King Hale (Robert De Niro). Despite his humble ways and wise words, it may surprise you that Hale prefers to be called ‘King’ by all and sundry, including his nearest and dearest.

Hale has been closely allied with the Osage for decades, even speaks the language, bless his heart. And, as a rancher, and a deputy sheriff, you would think that he’d have some interest in finding out what the heck is happening in Osage, in order to maintain peace and prosperity for his people, the people that he loves, the Osage?

You can probably sniff out where I’m going with this: okay, so maybe King Hale isn’t completely a selfless, wise old statesman, pillar of the community, titan of industry. Or maybe he is those things as well as a ruthless amoral kingpin. Maybe, when his lunkheaded nephew Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio) comes back from the Great War in Europe, maybe it’s Hale that encourages him to get close to Mollie (Lily Gladstone), because what else is a loose man good for, eh? You can’t have someone that looks like Leonardo DiCaprio just walking around alone distracting the womenfolk with his earthy ways and rugged looks.

He should really cover up, or smile more or something. From the start we get the clear impression that Ernest is none too bright. DiCaprio, throughout the film, maintains a downcast grimace which makes the character probably look even dumber than he actually was. The film constructs a portrait of a man cunning enough to acknowledge his self-interest, and brutish enough to harm or kill people himself when ordered, but not someone cruel or amoral enough to enjoy it.

And, this being a very complex piece of character balancing – a man who loves his wife and family, who nonetheless doesn’t see the contradiction inherent in helping destroy the people around them as well as his wife, when told to.

Ah lurve you but ma uncle said youse has to die so…

I don’t know how the film pulls it off. I am not entirely sure that the film actually does pull it off, but it’s definitely pulling something.

As is Scorsese’s wont, he goes to a lot of trouble building this world so that it looks like a real, believable time and place. There are of course plenty of scenes that both give a physical weight to situating this long-gone world as well as giving us a feeling that it’s substantial, that it’s not just empty sets. So there are big crowd scenes, and parades (including with the Ku Klux Klan proudly marching unopposed), and powwows. There’s also a lot of what I now am calling procedural shots or sequences.

I have no doubt he’s been doing it his entire career, and there’s no doubt there was plenty of it in Goodfellas way back then, but I only really noticed it explicitly in The Irishman, or at least I think I began to understand the impulse.

There is a thing that people do. There is a thing that older men do.

Of course it’s easy and lazy to joke that every time boorish men open their mouths and start expounding on some topic no-one asked about, especially around a woman, that they’re mansplaining.

If only it were so simple. Would that it were so simple.

Allow me to mansplain mansplaining to you, or at least “old man director overexplains everything” to you.

Imagine you’re walking down a street. You need directions to somewhere nearby. You ask someone “where’s that nearby Chatime?” They might just point, or, if they’re really helpful, look it up on their own phone and show it to you, without speaking, and then walk away.

Young people. They might do that.

If you asked a man of a certain generation, if it was in fact Martin Scorsese who was answering the call to action, he would verbalise a whole host and array of instructions as to how to exactly in space-time where you are situated every intricacy of every variation that you need to take in order to get to your destination. It would involve encouragements to exactly what speed you should be walking at, how many steps you would need to take in any given direction before changing trajectory, the qualities of the roads and footpaths, what you would see along the way, any obvious signposts with which to guide yourself, and pretty much a complete history of the entire area, including what businesses existed here before the Chatime moved in to that space.

You would be left, in no doubt, about everything relevant and irrelevant to the journey, even if it would have been easier for him to just point across the street where you can see the fucking place for yourself.

They say it’s better in storytelling to “show, don’t tell”. Well, why not do both? Why not show us something that happened, then go back over it in painstaking detail, then have people explain everything we saw with words, and then show us what happened again?

So much of this flick is procedural. We get the ins and outs of how certain things happened from beginning to end. As in, the uncle saying something to Ernest about how this person or that person should die soon, mostly because they were going to die anyway, and it’s only doing them a kindness anyway. Ernest then goes to someone else and says “how about you kill such-and-such, I’ll make it worth your while”. The other person grumbles about not wanting to do it, but then eventually tries to do it and fucks it up.

This then leads to scenes where Dear Uncle expresses his anger at Ernest fucking something up that was fairly basic, Ernest apologises, and then either goes back and asks the same person to try again, or asks that person to ask another person to eventually do the thing that Uncle King wanted doing.

The thing is done, usually resulting in deaths. Then something else fucks up, the uncle risks exposure, Ernest apologises again, then someone else probably needs murdering.

Rinse repeat fourteen more times. One person viewing this could be bored out of their fucking minds. Another could be edging towards an orgasm the more details that are revealed in painstaking detail, and delighting in the fact that it’s taking even longer and longer to get there.

If you recall one of the many famous scenes in Goodfellas, there’s a montage sequence set to the tune of Eric Clapton’s Layla, the aftermath of the Lufthansa heist is shown in a perfect tableaux of demonic fuckery. It’s succinct, it’s edited to follow the musical contours of the song, it’s kinda perfect.

We didn’t need to see or hear people planning what they were going to do to whom, and how, and what roads they were going to take to get there, what clothes they were going to wear, what implements they were going to use, the logistics of how you actually lift a person onto a meat hook, what the weather was going to be like that day, what order people should be murdered in, what they should do afterwards to celebrate etc.

But that was Scorsese thirty years ago. That is not the Scorsese of today. Today he is worried you might not understand exactly what happened when something happened. He’s terrified that you won’t get it. So he gives you everything.

At least an hour, and that’s being conservative, of The Irishman is people arguing over the logistics and the mechanics of some people planning on killing Jimmy Hoffa, something which in reality these characters never even did. And yet we somehow drown in the details of what cars they used, how long they drove around for, and what happened to the fucking carpet that was in the place where they (allegedly) shot him.

In Killers of the Flower Moon, a 3 ½ hour movie, it would be an absolute churlish churl who would point out that maybe two hours at least of the flick are nothing but process process process.

It's an old man’s affliction, but hey, it’s Scorsese. Everyone else cuts him slack, and I guess so should we, yeah?

An argument can be made, maybe should be made that a flick like this, about this horrific set of crimes, needs a complex explainer. That what happened justifies this kind of process and detail. After all, the whole reason the book was so successful, and the film has such resonance (I think), is because what these jerks did against the Osage stands in as a perfectly ghastly microcosm / diorama of adding insult to injury on top of the generalised genocides the first nations peoples of the Americas have suffered since colonisation, and all through the formation of their so-called greatest nation. Treaty after broken treaty, slaughter after slaughter, displacement, forced relocations, the Trail of Tears, Wounded Knee.; it’s never ending, and never ended.

And one tribe finally catches a break, and then they still get plundered and murdered for it. The (white) Man just couldn’t let them have it, not one cracker, not one thing going their way.

It is important to represent the array of entitlements that made it so Hale and his cronies could do this, legally and above board, despite the fact that they were openly murdering people and no-one gave a fuck, and they would have gotten away with it had not someone from Washington, being the Bureau of Investigations, under the wise guidance of J Edgar Hoover, pushed by President Calvin Coolidge, did something about it.

No-one in Oklahoma was going to hold King Hale to account, mostly because they all had their hands in each other’s pockets, and he was connected to everyone in the state through the law, through politics, and even as a Mason.

You read that right. The strangest scene occurs in this movie, so strange that I thought I’d dreamt it.

Uncle King Hale, miffed at Ernest for his folly, brings Ernest into the Masonic Hall. He bids him to kneel, and bend over. And then he grabs a paddle, and he spanks this grown-arse man, being Leonardo DiCaprio, to punish him for his stupidity. Presumably, also, spanks him for our amusement.

If you ever wanted to watch Robert De Niro spank Leonardo DiCaprio, well, now you can wonder no longer. Have at it, you weirdos!

It’s those interpersonal scenes that matter most in this movie, because that’s where the real meat of the movie is beyond the logistics and the what-happened-when stuff. Without the scenes of affection and reassurance between Ernest and Mollie, or Mollie’s sister Anna and her mum, and Mollie trying to maintain her composure in between seeing so many members of her tribe and direct family being picked off one by one, and with her ailments, I don’t think we would care. The supreme juxtaposition of knowing that something dreadful is happening, but not knowing that it’s the very people around you doing it, makes for strange feelings on the audience’s part.

She is the aching soul of the movie because, being Catholic, Scorsese does need people to suffer, especially the innocent. There are no shortage of scenes of Mollie suffering either like a bereaved Madonna in a pieta, or like a martyred saint. There’s no shortage of suffering or Catholic iconography.

There’s a set of scenes towards the end where people around King Hale’s property are seemingly either trying to put a brush fire out, or making it worse, hard to tell, but from Ernest’s perspective, through the wavy glass of his bedroom windows, he may as well be watching the demons and damned souls of suffering their eternal torments in the endless flames.

Could he be thinking of his own guilt in all the terrible things that have happened, that he’s done?

Nah. Too obvious. It would be like having a shot of a rat symbolise a character who was a rat at the end of a crime movie. The rat symbolises obviousness.

Performance-wise, it’s hard not to think that DiCaprio is again grubbing for another ill gotten Oscar. He’s not going to get one for this, because his characterisation, though appropriate in this outlandish yet true story, is pretty goofy. He also overacts atrociously in a few scenes, which just makes me think, nah, ain’t no-one can tell him shit these days.

Reel it in, Leo, you’re going too big.

Just like Will Smith. You think any director has the ovaries or the balls to tell him to do a take differently these days?

No way. No bitch-slappin’ way

De Niro manages to restrain himself mostly, which is nice. He manages to play the role straight without being able to lean on the physical menace he used to rely on for so many roles. Here he’s a tiny Boss Hogg figure who’s no less formidable, and no less capable of destroying entire communities and arguing that it’s in everyone’s best interests to give him what he wants, no matter how terrible.

Of course it’s Lily Gladstone as Mollie who will get the plaudits and the awards, and she deserves it. She’s so restrained and sly in this role, and though I hated watching her suffer, that only adds to the feelings of gratitude when she survives.

I can’t say whether this is the epic film it thinks it is. I have no capacity to ever think about watching it again. I guess it’s “important”. Americans need reminders of what horrors they’ve wrought, and those of us (non-indigenous) peoples who live in colonised lands need “oh, yeah, we did that” reminders of what we wrought too.

Because otherwise…

8 times I cannot figure out why Mollie didn’t eventually stab Ernest out of 10

--

“Oh, yeah? I mean, there might be a public outcry for a while. But then you know what happens? People forget. They don't remember. They don't care. They just don't care. It's just gonna be another everyday, common tragedy.” - Killers of the Flower Moon

- 181 reads