This shouldn't be happening, there, or anywhere. Please stop.

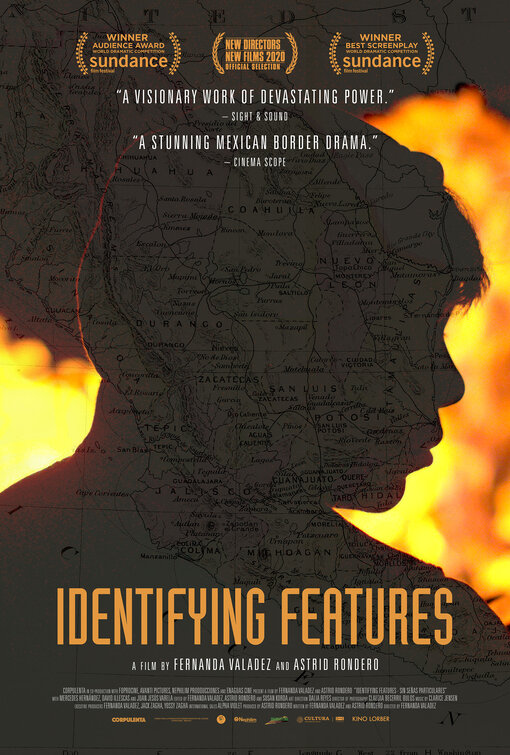

Sin Señas Particulares

dir: Fernanda Valadez

2020

I don’t understand. I don’t understand what is happening, what is depicted here, as happening in Mexico.

I understand government violence (well, when I say that, I say it from the safety of distance and privilege, in that I can intellectualise about it, but haven’t lived through it), I understand the concept that criminal gangs commit violence in order to control drug operations and maintain areas of control.

I guess I understand the concept of right wing or left wing paramilitaries, or religious nutters attacking villagers and villages, or ruling suburbs, or any number of things. I think I understand violence as a tool to make the survivors cower, and go along with whatever the group wants.

I don’t understand what is depicted here. Killing just to kill people, and not like serial killers or sadists or crazies or vampires. People, trying to get to El Norte (the States) from all areas of Mexico, being robbed, murdered and their bodies desecrated and burned, just for the hell of it.

And…it’s real, it’s what’s been happening for a long time in Mexico, and I find it terrifying, and I don’t understand it.

A recent film I watched about the Srebrenica Massacre (Quo Vadis, Aida?) during the Balkans War in the 90s, that was horrible, and terrifying, to see a group of people try to exterminate an ethnic group of people they don’t like. That’s horrible, too, but I can at least grasp some semblance of their mentality, of how they justify it to themselves, or try to justify it in front of a war crimes tribunal at The Haig.

I don’t understand this.

The perspective is mostly from that of a mother, Magdalena (Mercedes Hernandez), trying to find out what happened to her son Jesús (Juan Jesús Varela), who went up north two months ago, and haven’t been heard from since. She lives a humble farming existence on a small plot of land, and while she obviously fears for her son, she would understand the son’s drive to go El Norte, cross the border, maybe eke out a living and send some money home. The lure of the better life that only money and not being surrounded by apocalyptic violence could bring.

When he and his mate disappear, his friend having a distinctive patch of vitiligo on his forehead, making his body easier to identify for his mother, at least, Magdalena doesn’t accept that just because the authorities say that he’s dead, that he must be.

She’s fully aware that he might be dead. This isn’t false hope or delusion on her part. She has a weary kind of resignation to what has happened. But she has to know for sure. She needs certainty, a mother needs certainty, to bury her son, to bring him home, somehow, if she can.

The problem is, well, the gangs or cartels don’t make it easy. The sheer scale of what is happening is shocking, it shocks the conscience. It is worse than if there’d been an actual war, or civil war, at least. Every week shallow graves, and shallow mass graves are found, hundreds if not thousands of victims, in many cases disfigured to make them unidentifiable, in other cases burned in piles, then buried.

Why? I still don’t know. Armed crims stopping commercial buses, carrying serious weaponry and wearing surplus US army gear, robbing poor people for their pocket change or for their knock-off Adidas makes not a lick of sense to me. And then killing them afterwards?

When Magdalena hears about something that might have happened on a bus, a bus her son could have been on, she investigates as best she can, but everyone is terrified. The people at the bus company deny the bus ever existed. An employee, who speaks to Magdalena but is not seen, tells her that an indigenous man was seen at a nearby migrant shelter, who said he’d been on a bus, where the devil came and killed everyone, but spared him.

The people at the shelter, even there, are too terrified to talk about it, and someone we don’t get to see, but Magdalena eventually does, tells her where this old man can be found. But even she doesn’t trust Magdalena, fearing either somehow that one of the cartels is testing her, or that it could get back to them.

This is a level of fear at the lowest levels of society that you don’t usually get to see outside of totalitarian regimes. Although I guess I’ve seen films, set in Italy, showing the paranoid pervasiveness of the mafia throughout all levels of society, down to the lowliest shopkeeper or the most senior politician.

Magdalena’s journey takes her towards a tiny village called La Fragua, near Ocampo, at the same time as a young man recently deported from El Norte starts his journey back to his mother’s house in Ocampo. We get to watch Miguel’s (David Illescas) journey literally from the moment border control people tell him to go and not come back. It’s pretty clear in this long scene, with this chilling soundscape of an otherworldly horn blowing continuously, that this pretty much is the border crossing place on the Texas border. Miguel is played by an actor, obviously, but I don’t think everyone else was. There is a scene where he crosses a bridge or overpass, in the evening, and there are the lights of thousands and thousands of cars, of people trying to cross the border.

Somehow I don’t think that was staged either.

No-one wants to take either Magdalena or Miguel to Ocampo, by bus or car. No-one wants to go there. The cartels have killed the mayor, and pretty much everyone else. To what end, I have no idea. Magdalena and Miguel cross paths, and he offers her the hospitality of his mother’s place, which they reach, where there is no one alive.

These moments with Magdalena and Miguel are a brief respite from the relentless tension, though it does remind me that despite the spectre of cartel doom that looms over everything and everyone, plenty of people are kind and helpful to Magdalena along the way. There’s something about a mum concerned about her son that brings out the best in some people. Of course the cartels couldn’t care less, and will, we are given the impression, kill her just for existing.

Miguel’s sadness upon not finding his mum is multi-layered. He left home 5 years ago, and never would have come back had he not been deported. In that time he never sent money back. But also, he doesn’t have the illusion that had he stayed, he could have somehow saved her from a ruthless band of cartel executioners who need to kill a certain amount of innocent people each day or night or they can’t sleep well.

When they finally find the old man who can describe through a translating relative (he doesn’t speak Spanish) what happened, we only get part of the story in dialogue. The rest we’re meant to intuit from the horrifying imagery.

I say “horrifying”, in that it is imagery of The Devil, and of a fire running in reverse – though we, the great unwashed international audience, accept that in the eyes of the old man, he feels like only the devil himself could perpetrate such evil, we know it’s not the actual devil that’s bothering to run around Mexico killing people for their pocket change. The devil is way too busy for that, which is why he delegates and outsources as best he can.

What are we to make of this? When I speak of my lack of understanding, of my incredulity as to why so many tens of thousands of people have died in Mexico over the last 15 years or so, being able to blame the scale and enormity of the violence on an all-powerful, supernatural being would be tempting, comforting, even. We shudder to accept that people, reasonable people, would do stuff like this if they had a choice between killing people for no reason, and not killing them. A devil, or The Devil, countermanding their will, controlling them, forcing them to do this evil against their will, that somehow becomes more comprehensible.

In the old man’s words Magdalena finds something close to certainty as to what happened to her son. But then the true ending of this flick, after she urges Miguel to come and live with her, when he looks like he has nothing left to live for, presents a third possibility she hadn’t considered, which is more devastating that anything I could have imagined.

This is a heartbreaking film about something terrible. How can people bring themselves to make such beautifully composed, considered, exquisitely shot films about something so desperate and horrific? Mercedes Hernandez’s performance anchors this film, with her sadness, with her determination to find out what happened, with her horrified resignation at the end.

This is a devastating film. I wish somehow it helped changed things in Mexico, but I can’t see it happening. It’s also the second film I’ve seen this year that has a translated title that has the opposite meaning of what the original title was, and yet both movies are about the evil humans are capable of. The Spanish title of the flick is Sin Señas Particulares, which literally means “no identifying features”, and yet the English title is Identifying Features. Go figure. It’s a great film, but be warned, it’s deeply depressing.

9 times out of then people need no help to do good or evil out of 10

--

“No matter what they tell you, don’t make the same mistake.” - Identifying Features

- 857 reads