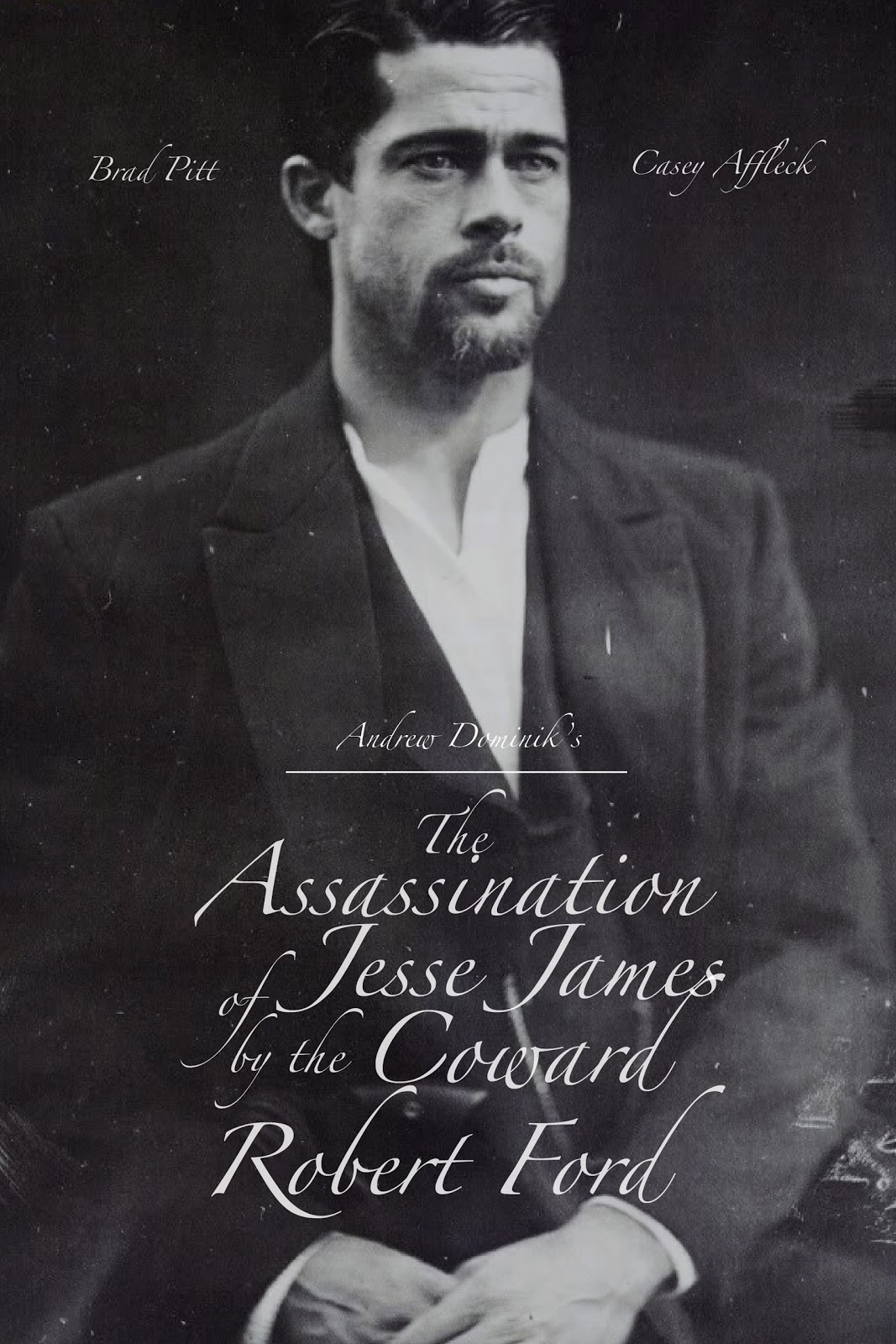

Good job making Brad Pitt look like a legend from a bygone era, photoshoppers

dir: Andrew Dominik

Assassination is one of the most beautiful and mournful films you’ll ever see. It is long, and sad, from its first immaculately composed and photographed scene to its last. None of which will make it any more enjoyable an experience for the general audience that will be bored out of its collective fucking mind.

Though anyone seeing the film should know exactly what it’s all about from beginning to end from the title alone, what they might not expect is that the flick is really about both the deconstruction of a myth and the deconstruction of a person’s soul. Not a lot happens in the 160 or so minutes of screen time apart from the falling apart of a curiously larger than life persona.

These are the twilight years of Jesse James and his gang. At the advanced age of his mid thirties, James is plagued with physical and mental ailments that render him something of a paranoid wreck, and unknowable to the people around him. As the persistent voiceover keeps telling us, he trusts not a soul, and moves his family at a whim at the slightest hint of trouble. He moves between Kansas, Kentucky and Missouri, always restless, always harried even if the law is not on his trail.

The last of the guys he can bring himself to trust when he isn’t planning on killing them, amount to cousins or close acquaintances. One of them, Robert Ford (Casey Affleck), has an almost girlish affection for James, bordering on worship. Actually, it’s not bordering on; it’s out and out adoration. But the James he knows from the penny dreadful serials and from the legend arising from his many crimes is nothing like the James he sees before him.

James and his elder brother (Sam Shepherd) plot and carry out one robbery during the timeframe the film encompasses. The job does not go especially well, but it would be the last time James could tolerate being around this many people. From then on he is at war with himself, alternating between seeking out the company of people he can trust, and killing those who are too close for him to be comfortable.

Yet he is a devoted husband and father, loving his wife Zee (Mary Louise Parker) and his children with unalloyed affection. The peace of the home and hearth is not enough, however. It never is.

Ford’s love of James verges on almost a physical desire. At one point he creeps up on James in the bath, compelling James to ask the eternal question “Do you want to be like me, or be me?” With the almost naked passion with which Ford watches James’ bathtime fun, it’s a wonder.

James doesn’t really want this puppy-dog love from Ford, but at first at least does not condemn him for it. As time passes, though, and we see that James’ path to the grave grow ever starker and closer, his tolerance of Ford’s adulation turns to contempt.

And why wouldn’t you be contemptuous of the coward Robert Ford? Like many a protagonist or sidekick character of the crime genre, Ford is the weak, spineless guy who thinks, like Raskolnikov from Crime and Punishment, that the mere process of killing another person will somehow elevate him to the status of a god. The syllogism follows that since James is a god to him, and James has killed people, then to become like James he has to kill people too, doesn’t he?

Affleck plays the more complicated role here. It is very hard to make a character like Ford’s sympathetic. And the character has to be sympathetic if the film is going to work on anything more than a visual basis. James has to remain something of an enigma, even as his myth and mystique is deconstructed before our eyes. Most of the time Pitt conveys this well by simply not talking and looking tortured. Pitt, for once, does well with the physical portrayal of embodying a character. Shame that the illusion is so often shattered whenever he opens his mouth.

I have to say, as much as I wanted to love the film, Pitt did manage to irritate me sufficiently that my feelings for the film became somewhat muted. I’d be fine with it for a while, then he’d do something out of character that I know wasn’t in the script that would keep bludgeoning the point home with a railway spike to the head’s level of subtlety that he’s Brad goddamn Pitt playing some character poorly yet again. It required him to be subdued, and he just can’t bring himself to do it.

It must have been hard for director Andrew Dominik. He dazzled Australian audiences with Chopper a bunch of years ago, and here he’s been given an incredible opportunity and more of a budget than any Australian (well, like many of our exports, he’s actually a Kiwi) director usually deserves. He used it to craft a film, really craft something beautiful. And then he’s forced to have someone like Brad Pitt in the lead, since he’s the producer. And how often do you think Pitt took advice and constructive criticism on his performance from Dominik?

In this instance, it was probably Angelina Jolie’s turn to sit in the chair just off set stroking the Persian cat like she was a Bond villain.

It’s so unfair. Speaking of unfair, I’m probably being harder on Pitt than he deserves. You don’t yell abuse at the kid that comes second in any Special Olympics-type event. The fact that they’re competing is justification enough. It’s just that the voiceover narration does so much of the heavy lifting, and Pitt perfectly encompasses the physical needs of the character’s portrayal such that the times when the performance becomes too broad it hurts all the more.

The film’s passage to its inevitable conclusion becomes agonising the further it goes on. Helped by another superb collaboration by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, the soundtrack fosters the elegiac mood instead of beating you over the head with it (unlike the obtrusive and painful There Will Be Blood soundtrack, as an example). I mean agonising in a good way, if that is at all conceivable.

Once Ford is resolved, for his own and for external reasons, to his path, we see the pieces and circumstances falling into place that will result in James’s famous end. The most curious element we find is that James, yes Jesse James himself, does not seem averse to the thought of his own death. In fact, thoughts of death seem to have overwhelmed and consumed him. And though he takes steps to ensure his own survival (by taking out those he thinks are plotting to take him out), he seems to almost want to be killed by the time Robert Ford works up the courage (or is it cowardice) to finally put a bullet in the murderous legend.

It is a surreal story, no less strange for being a true story. Ford did kill James, and lived with the aftermath of fame and infamy it accorded him, and meets his own end in a curious fashion. It is a strange story told lyrically, without hurry, in a painstaking, loving fashion, with as much affection for its characters and for the cinematic medium as it can muster.

Don’t let the setting and the era frighten you: it couldn’t be less of a western if it tried. It’s an anti-western at that, completely eschewing the usual dynamics that crop up in the revisionist genre entries we’ve been seeing for the last decade or so. The script is meticulously put together, giving an otherworldly rhythm and quality to the story as told. There are few if any anachronisms (apart from Pitt laughing like a retarded Malibu surfer in a couple of scenes) to distract us from the epoch. This is, after all, a story about men no longer able to live in this post-Civil War America the way they want to or are able to, for whom fame/infamy is too a terrible burden to suffer to live.

With two such complicated characters as Ford and James, you’d think it’d be the occasion for screaming matches or overacting at the drop of a bowler hat. But the story (generally) is told in such a restrained fashion that the little touches sing out and show how complete the director’s mastery is of the material. Roger Deakins as the cinematographer does deserve plenty of plaudits for visually telling the story in such a rich fashion as well. The usual fall-back position of any cinematographer doing a western is regular postcard shots of wide open vistas and soaring mountain ranges

The crucial event of Jesse James meeting his maker is a scene so pregnant with tension, so fraught, so agonising despite how little happens that it became almost unbearable to watch. Pitt, Affleck and Sam Rockwell as Ford’s elder brother Charley, who is obsequious to a fault at all times around Jesse, enmeshed as they are in so many impossible dynamics and fears and hopes, raise the scene above anything I could have imagined for such a flick or any other flick.

It’s just such a shame that I couldn’t enjoy Pitt’s performance as much as I wanted to. If I’d been able to, I would have considered this to be one of the most amazing films I’d seen thus far in my 35 or so years stumbling around this planet. As it stands, it’s just a pretty good film from the unlikeliest of sources.

7 ways in which all westerns have always had homosexual undertones way before Brokeback Mountain ever appeared on the scene out of 10

--

“My love said she would marry only me and Jove himself could not make her care, for what women say to lovers, you'll agree, one writes on running water or air” – The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.

- 4481 reads