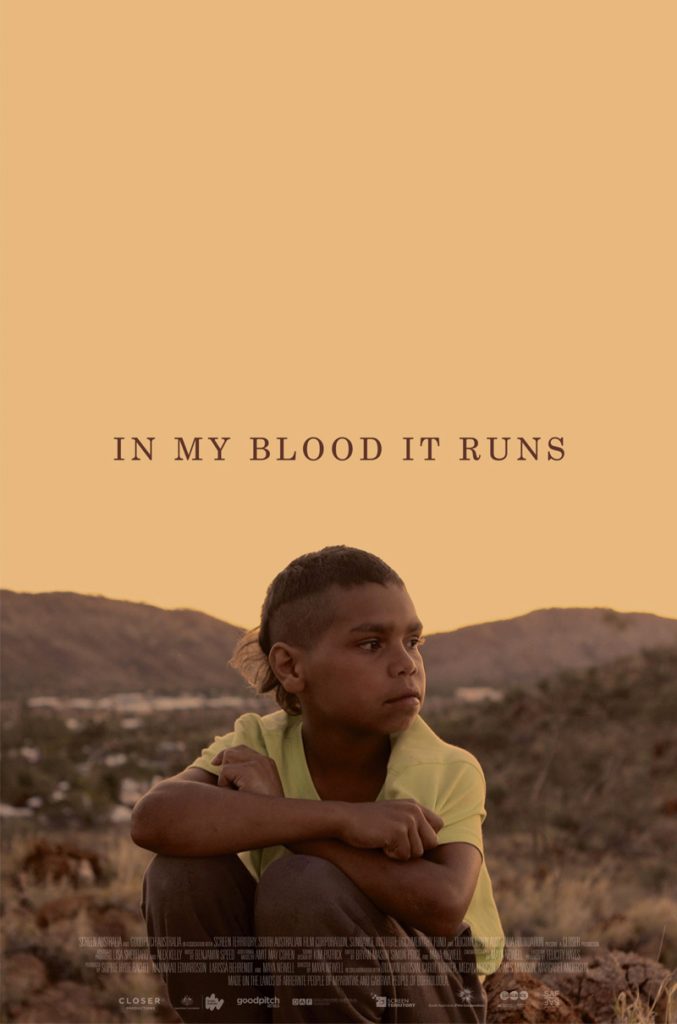

Good luck in this hard world, Dujuan, to you and your family

dir: Maya Newell

2020

This documentary, called In My Blood it Runs, is a timely film, because its story has been relevant for at least, oh, the last couple of hundred years or so. The problems Dujuan and his family face are the problems all First Nations people face, but the film focuses of course on this one boy in order to represent the larger issues at play. If we can appreciate the world that he lives in, maybe we can grasp the significant obstacles placed before him and the people he shares a connection with.

And in case a theoretical reader of such a review is already getting an outrage boner muttering under their breath “As if First Nations / Indigenous people have any fucking problems, we give them EVERYTHING and they set fire to it and steal our hard earned jobs and then don’t work because they’re fucking lazy” etc etc bullshit, even though this person would in theory benefit most from such an intimate portrayal in such a doco, they are the least likely to appreciate it.

It requires empathy, and the ability to appreciate the humanity of people you reflexively might not like, and yet don’t understand why you can’t, therefore you spend your life maligning them in public, online, in Parliament or as columnists, for shits, giggles and clicks, all the while telling yourself “they’re the problem, they’re the reason why I don’t like ‘em, nothing wrong with ME”.

Don’t go changing. Not as if you’re capable, anyway.

What runs in the main subject’s blood? His ancestors, his history, the trauma of colonisation, the deep persisting wound of the Stolen Generation, the expectations of his family and people, but also, the healing power that he keeps being told he inherited from his grandfather. Now, I am more cynical than most, and more unfair than many, but this isn’t the place to debate the pros and cons of whether he genuinely possesses the power to heal people or not. It’s not like he’s telling people to use his powers at a cost of $299.99 per hour, instead of any other form of medicine, or that he can cure the coronavirus with colloidal silver and a laying on of hands. There’s something simpler and more complex at the same time.

He’s a kid, he’s just a kid. His people, at least on his mum’s side, are Arrente, from north of Alice Springs. Mostly, it’s his nan bringing him up. But, like always seems to be the case, she has a fair amount of kids to look after. It’s a lot to ask one Nana to do. And Dujuan’s mum has another sibling on the way.

Schooling is not easy. You can argue about ratios (of teachers to pupils), or about structures which don’t allow for someone from his background to get the support that he needs, or the relative chaos at home, whatever the argument, Dujuan is falling behind. He is neither as proficient in the Arrente tongue that his nana struggles to instill in him, nor the tongue of the colonial oppressors.

And some of the stuff being taught out of outdated textbooks is heartbreaking. I have to assume the moment I’m thinking of was done for effect, but it compounds the sense we get that the school isn’t equipped to be a supportive environment for someone like Dujuan, for anyone like Dujuan.

The doco doesn’t have to underline it, because it’s plain for all to see – the more he falls behind at school, the less interest he has at being at a place he feels he is not wanted; the more he feels he doesn’t belong, the less he actually ends up being at school. The more his nana has to search for him in the early hours, as he rides around alone on a “borrowed” bike, or hangs out with kids way older than him in the heart of Alice Springs.

We know no good will come of this. Even with the love and support of family, there’s only so much they can do to keep him on the straight and narrow, and by straight and narrow I mean keep him out of juvie and eventually jail. That pipeline of incarceration isn’t going to fill itself.

Dujuan has a camera himself, and often asks questions of his mum, auntie and nana, but when he asks the questions, there’s not a lot to indicate why he’s asking, as in what prompted him to ask, if not the director herself. He also seems to be a bit indifferent to the answers. This was clearly filmed over a long period of time, at least a couple of years, which we track from the changes in Dujuan’s hair lengths or hairstyles, but it’s enough of a length of time to get a sense of the lives of many people.

Dujuan’s mum explains at one point the circumstances around becoming a teenage mum with Dujuan’s older brother and then him, and the breakdown of that relationship, but doesn’t go into the specifics. One of Dujuan’s aunties is hospitalised, with a wound to her leg, but other than the family being freaked out and visiting her, and Dujuan trying to use his healing to help her, no mention is made of the specter of domestic violence that lingers over all. One could argue about whether it’s better to leave out the explicit mention of it, or just having it hang over things as an unanswered question, but since this flick is from the point of view of an eight year old kid, I’m not sure giving One Nation style bigots more ammunition to bellow about the general unworthiness of our indigenous brothers and sisters would help matters either.

Footage is spliced in of the treatment of indigenous kids in youth detention, the infamous torment from the Don Dale facility, because this film is making it plenty clear that ignoring kids like Dujuan, not supporting families like his means the limited imagination of the state only looks towards punitive measures as potential solutions: threaten the family with loss of custody of Dujuan and the other kids, or cast rose petals of invitation onto the path of making sure Dujuan ends up being the latest resident of a place like Don Dale, where 100% of the incarcerated are indigenous.

In case the documentary didn’t make the point clearly enough – 3 per cent of the country’s population are indigenous. 100 per cent of the kids in juvenile detention in the Northern Territory are indigenous.

It’s harrowing to consider, and it should be. The film is asking us to consider how easy it would be for Dujuan to slip off an already slippery path and become another dehumanised statistic.

Of course, considering the fact that Dujuan himself spoke in front of the United Nations last year, this documentary, thankfully, goes down a different path. It is agreed by the families that Dujuan would benefit by living up further north, 1200 kilometres or so, with his father for a spell. I know that the makers aren’t making the point that Dads are the only thing keeping Kids out of jail, but it does make the point that overwhelmed mums and nanas sometimes need to share the weight of looking after kids where they can.

Is it too simplistic, too “neat” that Dujuan thrives? Starts doing better at school, stops acting out as much, is happier? Maybe. But the flick isn’t a lecture about what should happen to save ever single indigenous kid in Australia – it’s an intimate and quiet look at one indigenous kid’s life, and how it went in a more positive direction than it does for many other kids.

It’s quiet, but powerful. We should wish for more kids like Dujuan that their story follows a happier path too, and strive to encourage the various governments to better support where they can without resorting to the same old bullshit that exacerbates the problems they face, the terrible health and legal outcomes, and the business as usual approach that we should have abandoned long ago.

Because this victim-blaming shit isn’t getting any of us anywhere.

8 times the only thing that runs in my blood is gin and some rage out of 10

--

“You’re only going to end up in two places: jail cell or coffin.” – happy birthday, kid – In My Blood it Runs

- 1729 reads