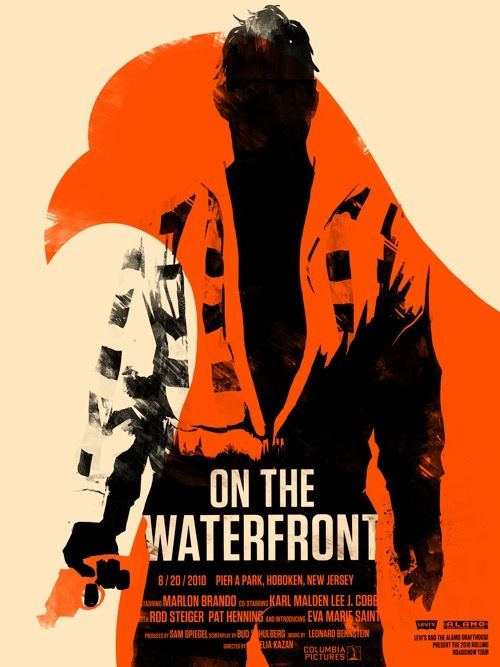

When he was a young god...

dir: Elia Kazan

1954

It’s a bloody shame that possessing too much knowledge makes it impossible to just talk about a great film and call it a great film. Either that, or you can put it down to arrogance, pretentiousness, or affected hipsterism. Whichever and whatever combination thereof that I’m afflicted with, I’m too aware of the history behind this picture to be able to blithely review it like it’s just any film.

Sure, it’s a film like any other. Although, it won a bunch of Academy awards, and it contains one of the greatest performances by Marlon Brando that you’ll ever see. And it casts a mournful eye over the waterfront upon which it is set, and the cowardice, greed and cruelty that conspires to render good men either dead or useless at the hands of a corrupt union.

And it’s directed by a man who made some great films, like this, Streetcar Named Desire, A Face in the Crowd, Splendor in the Grass, and Gentleman’s Agreement; films which I’m sure all the kids of today are big fans of and love to hear quoted in the latest emo and rap songs illegally downloaded onto their iPods.

But Elia Kazan also named names during the Communist witch hunt era, lending credibility and legitimacy to a process that should never have possessed a skerrick of either, and continued to work and live a happy, productive life after condemning others to blacklisting and misery.

For a man who received plenty of awards during his life, perhaps it might strike some as strange that he required honouring at the 2003 Oscars with a lifetime achievement award, where many of the crowd refused to applaud or even stand for him. Talented director, traitorous fiend, or both?

How do you separate the off-screen antics of a director or a screenwriter from their films? Is it possible or moral to judge Kazan’s or Roman Polanski’s movies without thinking about their actions, which are completely independent of their movies?

For some people, it’s easy and a no-brainer: who cares? It’s the “if someone makes a film that I find entertaining for a couple of hours so I can forget about the fact that I have only one working kidney through decades of alcoholic binge-drinking, and a wife who sleeps with the guy who used to bully me at school, then I don’t care if the director is a child molesting serial killer” approach.

For others, like a Canadian friend with whom I often have this argument, it’s never justifiable or allowable to consider the artwork independent of the maker’s actions. If a scumbag makes a great work of art, they’re still a scumbag, and praising one of their films, regardless of its merits, is a criminal act of moral relativism. You contribute to a scumbag’s purse or legacy by watching or praising their antics on the screen, whatever the end product. And it gives de facto acceptability and credit to someone for being an artist that you wouldn’t give if they were your garden variety criminal.

It’s a valid point, even if I don’t feel entirely comfortable with either position.

Wherever on the spectrum you may be personally, the main issue regarding praising or damning On the Waterfront is this: Elia Kazan named names in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee; names of people who were either suspected Communist party members or sympathisers. His claim has always been that these people’s names were already on the HUAC’s lists, so that his actions were only a formality.

Some of those people mentioned and blacklisted: directors, actors, screenwriters, struggled to feed themselves afterwards for decades. But Kazan and screenwriter Budd Schulberg, who also named names, continued to get work, strangely enough. And On the Waterfront is seen, quite rightly by some, to be an elaborate self-justification on the part of the cowardly pair.

We first see Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) calling a guy out of his apartment. The guy is scared, because he suspects someone is out to get him. He’s right, because a somewhat naïve Terry is tricking the guy into letting his guard down. A few minutes later, the guy takes a dive from the top of a tall building.

Gravity is not his friend. Stinking of guilt and fear, Terry knows his place in the scheme of things at the docks. The poor unfortunate who flew but temporarily was about to testify to a commission about the influence of organised crime in the union, or the ‘local’, as it’s usually referred to. Terry does odd jobs for the local as an enforcer, a bruiser, but, seeing as he’s considered a bit of a punch-drunk palooka from his years as a boxer, he’s not exactly privy to the machinations at the top of the hierarchy.

Terry’s brother Charley ‘The Gent’ (Rod Steiger), however, does have pride of place within the local. Highly respected for his intelligence as applied to criminal ends, Charlie is the right hand man of the loathsome Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb), who rules the union with an iron fist.

And what a union. Under Johnny’s benevolent leadership the union indulges in every form of corruption and graft. Murder, extortion, intimidation, theft and littering all occur with the union’s instigation, with the silent compliance of the union’s members and with the indulgence of the community.

How has this circumstance arisen? The union’s leadership is mobbed up, and both gets its orders, goons and guns, and kicks back money and goods to the local mafia representatives. The workers have no recourse for dissent, because they have to pay bribes even for the option to work. The local community is entirely dependant on employment at the docks, for which there is no job security day-to-day for a man’s family. Of course they’ll keep their mouths shut. They have no other choice.

The guy who had a sky-diving accident has a sister, Edie (Eve Marie-Saint), who returns home from college to mourn at his funeral. The reason Edie’s father, who works at the docks, sends her to college is so that she doesn’t end up married to a guy from the docks.

Naturally, she’s the perfect love interest for Terry. But she’s more than a love interest. She wants to know why her brother died, and who was responsible. The closer she gets to Terry, the more obvious it becomes to her and to us that Terry is knee-deep in murderous shenanigans.

Yet Terry has two things in his favour: a conscience and a complaint. This complaint has to do with the way in which he wishes he could have been something more than a fall guy and an enforcer for gangsters. Sure he blames himself, which is the source of much of his tension, but he blames his brother as well.

The film’s most famous speech occurs between Terry and his brother, in the most tense of scenes as Charlie is meant to be sending Terry to his fate, or to convince him to keep his mouth shut. It’s such a tremendous speech, and delivered so well that it deserves being quoted:

Terry: Remember that night in the Garden you came down to my dressing room and you said, "Kid, this ain't your night. We're going for the price on Wilson." You remember that? "This ain't your night."

My night! I coulda taken Wilson apart! So what happens? He gets the title shot outdoors in the ballpark and what do I get? A one-way ticket to Palooka-ville! You was my brother, Charley, you shoulda looked out for me a little bit. You shoulda taken care of me just a little bit so I wouldn't have to take them dives for the short-end money.

Charley: Oh I had some bets down for you. You saw some money.

Terry: You don't understand. I could have had class. I could have been a contender. I could have been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am.”

Beautiful. I know it’s become such a cliché, but it’s such a superb scene, with Steiger and Brando playing it better than it ever could be played or ever will be again.

Speaking of beauty, I don’t think it stretches the realms of accuracy to state that Brando here sets the perfect standard of masculine beauty in American cinema revealing all at once the brutishness and vulnerability that he would never have for the rest of his career. When you think of the monstrosity he would become, and just how superbly he embodies this conflicted character here, it’s a crying shame.

But his travails are not yet done. The union keeps killing its unruly members, and the local two-fisted, hard-drinking, chain-smoking priest Father Barry (Karl Malden) berates the men again and again that their turning of a blind eye is an offence to Christ himself. Each time they let one of theirs be killed is another Calvary, another Crucifixion on the docks. And he stands and takes his lumps even when the cowardly goons have the temerity to attack him as well.

Even though he’s the one reading them their last rites when they’re killed, the only one trying to change things, to get them to look beyond their next pay packet.

This being a deeply Christian, deeply anti-union, anti-thuggery tale, Terry must have his own Garden of Gethsemane, his own Stations of the Cross. It is not with violence, though he’s still more than capable of knocking out any of the goons Johnny sends after him, it is with forbearance, with doing The Right Thing, and enduring the ensuing onslaught that Terry can finally get the ‘class’ he craves.

The other local members, being (to be kind) afraid, or (to be unkind) sheep, look to anyone to find out what they should do, being unable to think for themselves. But the flick depicts them as being worthy more of pity than contempt, for they know not what they do, unlike Johnny and his henchmen, who are venal bullies. If the workers could put aside their fear, the mob loses its power over them, and change can happen.

Can Terry survive long enough to give them an example, to show them that a man can stand up and go on, no matter what they threaten him with? Will he get to live the vision he has of the future, which includes shacking up with Edie and getting paid to not lift a finger like he was used to when he was the brutal belle of the ball? Or will he actually have to start working for a living, if the local goes legit?

Well, let me not spoil a film from over 50 years ago for you. Everyone deserves to see this amazing flick, even if it plays out as a long and self-serving justification for naming names and ratting out one’s friends and co-workers. Can we believe that the Communist infiltrators and unions of Kazan’s day were as murderous and powerful as what he depicts here, making Terry a kind of Kazan stand-in, who does the right thing for the greater good?

There’s no denying that many unions, from the days of Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano onwards were controlled by the mafia. There’s no denying it. And there were certainly members of the Communist Party and so-called fellow travellers in Hollywood in all aspects of the film production business. Equating the two? Unifying the two? I’m not so sure.

But calling the flick an extended apologia for HUAC rats is also inaccurate. The original screenplay was written by Arthur Miller before he was blacklisted, and he certainly had no interest in vilifying the unions or lionising the namers of names (although he was replaced by Schulberg, who was definitely a namer). The story was also based on a series of articles by journalist Malcolm Johnson, who took a long hard look at the lives of the longshoremen and chose to write about it in the hefty yellow journalism form of the times. The priest was based on an actual guy, Father John Corridan, whose primary concern on the Jersey waterfront was working with these doofuses in order to organise labour a bit differently.

And then of course, despite the fact that he won an Oscar for his performance, Brando practically did everything he could to fuck his performance and the making of the film up. He was notoriously difficult to work with, and would leave daily for therapy sessions, making even the most famous scene something that occurred with the help of stand-ins and extras.

Yes, he was a great method actor, yes he defined cool post-The Wild One for generations, and sure he exuded a brutish sexuality. But he was also mad. Stark raving mad. And not very bright. Oh, and he was a sex-addicted, bisexual compulsive obsessive liar who couldn’t be bothered learning lines or taking direction, who preferred to provoke directors with his childish and insane demands.

But he was great here, in a performance he himself didn’t like. There’s a reason why the film is considered iconic, and why Brando is still considered one of the greats, back before he became an actual island, let alone bought one near Tahiti.

There’s a reason that he reminds everyone, with a hint of sorrow, that they too were contenders themselves, before they let their own short-sightedness, greed or fear scupper their chances of being who they wanted to be.

10 lunatic Brandos screaming “I’ll get you, you bimbo!” out of 10

--

“Conscience... that stuff can drive you nuts!” – On the Waterfront.

- 3200 reads