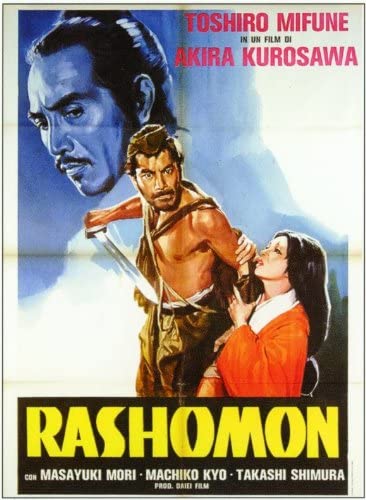

Doesn't this shit look classy

dir: Akira Kurosawa

1950

The Kurosawa fest continues. One of the most famous but least seen films of the last fifty years deserves a review, don’t you think. And since I saw it for the first time a few days ago, now seems like the prime time to launch into another pointless diatribe about a film few people will be inspired to run out and see.

Rashomon has been quoted as an influence in cinema for the last million years, or at least every time a story presents different versions of the ‘truth’. That’s the ‘truth’, as opposed to the truth. The simplest way of explaining this concept is the assertion that there really isn’t any objective truth because people see and experience events subjectively, as well as the fact that they lie to serve their own agendas.

So, now, every time a film shows a sequence, then shows the same event from another point of view, they bloody well are contractually obligated to mention Rashomon. The Usual Suspects? Rashomon. Wonderland? Rashomon. Hero? Rashomon. Dora the Explorer? Rashomon.

It would be less tiresome if it were actually true. Rashmon’s ultimate point wasn’t about this lack of universal truth, or our inability to have certainty about what really ever happens. The point was about whether there is any point in the continued existence of humanity. Whether we’re ever really going to be able to put our pettiness aside to at least have some consideration for each other.

The barbarism of the world as depicted in any of the alternate realities is the one constant: it’s a selfish, vicious and venal world, with everyone out for themselves. It’s messy, clumsy, desperate, and in the words of that mainstay of Japanese society, Thomas Hobbes, life is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. But there still remains a glimmer of hope.

The film begins with three men finding shelter during a terrible storm at the Rashomon Gate. Two discuss a horrible crime that has been committed, and argue over its meaning and the impact it has had on them. The third goads them into finding out what this story is.

They are a woodcutter (Takashi Shimura), a priest (Minoru Chiaki) and a peasant (Kichijiro Ueda). The woodcutter and priest know some of the details of the story, the peasant keeps baiting them and being generally irritating.

A samurai is dead, a bandit has been caught with the samurai’s sword and horse, and the samurai’s wife has been assaulted. Four different versions of events are presented to us as the three men at the gate discuss what must have happened.

In front of the authorities, the bandit Tajomaru (Toshiro Mifune) tells his version of events; that upon seeing the samurai traveling with his wife Masago (Machiko Kyo), the bandit is determined to have his wicked way with her, but not to kill anyone. He tricks the samurai and ties him up, then attacks the wife. Afterwards, he gives the samurai a chance with a duel, which he wins. Case closed.

But Masago has a different story. The attack remains the same, but in her version the samurai’s death is accidental. She doesn’t really recall how it happened definitively, but she recalls that he regards her with hateful, cold eyes for her dishonour.

The court is told another version, when a medium apparently contacts the spirit of the samurai and has him tell his story himself. In his version the wife and bandit are both complete pricks, and the samurai kills himself in shame.

The three men at the gate argue in between each version, mulling over the unknowable nature of the truth, and the likelihood of each version’s truth. Certain details of the crime have different impacts, almost like clues. The use and location of a valuable dagger plays a seemingly important role. They argue as black sheets of rain continue to pour down in a constant deluge.

The last version shown to us, as told by the woodcutter, is meant to be the true version, but even this is suspect because of his own involvement. At this stage it seems like the final point to be made is the one the peasant insists upon: that all humans are liars, that we’re all in it for ourselves, and devil take the hindmost. When he deduces with glee that the woodcutter himself has committed a crime linked with these events, his joy is complete and he goes on his merry way.

The priest, whose faith seems the most shaken by events, finds solace in a kind act performed by the woodcutter, which restores some of his faith in humanity as the men go their separate ways.

And what do we come away with from this film? For a film from 57 years ago, it holds up pretty well, but the expectation of the viewer coming to something that’s meant to be an absolutely classic of the medium means someone could be confused as to what the big deal is about. Even though it’s based on two Japanese stories from one of Japan’s revered writers, Ryunosuke Akutagawa, it doesn’t really sit comfortably in the history of Japanese cinema. It did bring both Japanese films and Kurosawa himself to the attention of the world, with the film winning the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, on the other hand.

Still, it’s fascinating and messy. Its messiness and its desperate humanity, devoid as it is of the usual elements of Japanese film dealing with duty and conformity and shame and everyone wanting to commit suicide, is what really makes it such a classic. It’s a very low key story about very low level players. This isn’t the assassination of JFK at Dealey Plaza in 1963. But even that event shows how even something we should have had an absolute answer for, witnessed by hundreds, is still elusive to us.

It’s an undeniably well made film, it’s hard to fault the acting, although mainstay of Japanese films Toshiro Mifune overacts like he does in everything. It has more in common with silent films than other films of the era, but it could also suffer from high expectations.

With Rashomon we see the effect that human selfishness and uncertainty has on a group of harmless simpletons. They’re all villains, they’re all innocent, no-one is completely blameless, but they are capable of moments of grace. Something which gives hope to the rest of us, too.

7 reasons that there’s no need to fight over me, ladies, out of 10

--

“Not another sermon! I don't mind a lie if it's interesting.” Neither do I, Rashomon.

- 2991 reads