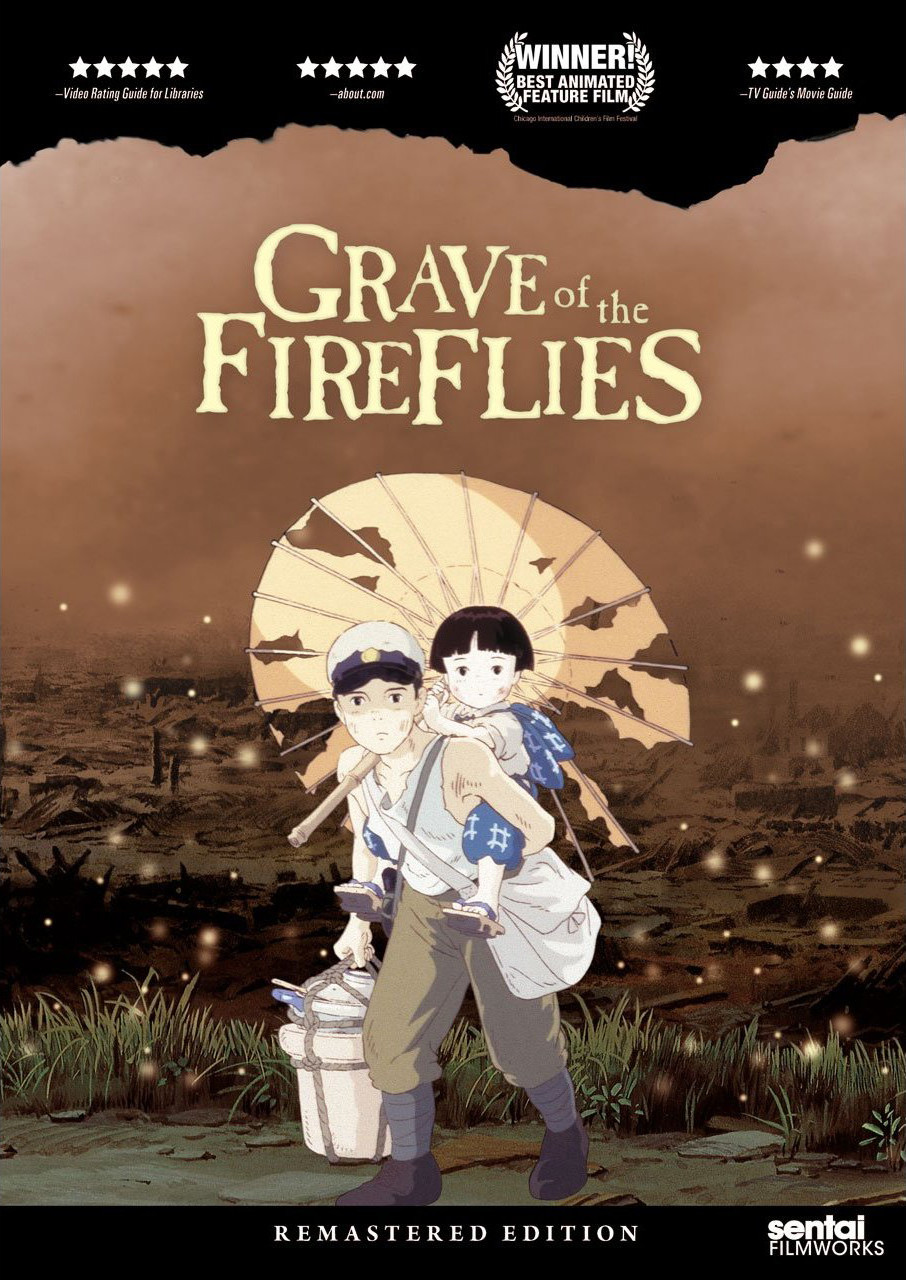

Just looking at this image makes me tear up

dir: Isao Takahata

1988

For all the pop culture popularity of Japanese animation, it still has a pervasively negative reputation. The main reason for this being, of course, the relatively small percentage-wise amount of anime that seems to be exclusively created for the purpose of creating violent stroke material. Anyone confused as to what I mean by ‘stroke material’ should know that I’m not referring to people having aneurysms or lapsing into comas.

In the same way that it would be inaccurate to say that all French cinema is basically films like Irreversible or Baise Moi, it’s unfair to tar Japanese animation with the hentai / giant robots / tentacle / schoolgirls brush. Sure they play a part, but much of it is just about telling a story.

Grave of the Fireflies is a heartbreaking entry in the genre, which has nothing to do with science fiction or girls having their underwear stolen by demons. It is a simple story (on the surface) about a brother and sister trying to survive in Japan during World War II. It has recently been given the royal treatment on DVD (Madman), which is why I felt inspired to write about it now, having just purchased it. The two disk set certainly is worth the purchase price for the film alone, but contains a plethora of worthwhile extras that sweeten the deal even more.

For a film of such beauty in which nothing much happens apart from the long, idyllic march to the grave, the makers have transcended the basic elements that constitute our expectations (at least mine as a non-Japanese viewer) of animation and crafted a story no less poignant or evocative than any live action film. Constructed with an incredible amount of craft, each panel seems to have been lovingly painted by people who had an infinite amount of time on their hands, which is obviously not the case.

Put together by the famous Studio Ghibli (directed by Isao Takahata, and not the ‘master’ Hayao Miyazaki) it exemplifies all the trademarks of that studio’s work which, bizarrely enough achieves everything Disney wishes it still could but never will again: great looking animated features that tell great stories and are massively, commercially successful. The irony of course being that Miyazaki created the studio having been inspired by the earlier works of the Mouse House in no small part.

Studio Ghibli most recently received much acclaim for Spirited Away, another amazing, distinctive animated movie which compromised none of its vision to achieve its goal: tell an amazing story and connect with the wider audience. Of course it remains a niche concept for Western audiences, but the film sold more tickets than Titanic in its home country. Of course it’s unfortunate that Titanic is still the benchmark for these things, but still.

Before all that massive relative success, they put out Grave of the Fireflies in 1988, based on a book by Akiyuki Nosaka. The film tells the sad tale of brother and sister Setsuko and Seita, cast adrift into the wilderness of Japan after the death of their mother and the destruction of their home. The occasion for these festivities is the fire-bombing of the city of Kobe, as part of the massive overall bombing campaign in the dying stages of the second World War.

If you suspect that the point of the film is to paint the US as bad then you’re getting your panties in a bunch for nothing. The military presence is distant, a boogeyman at the edge of consciousness until the inevitable bombing begins. People, being the adaptable creatures that they are, try to go about their daily routines unfazed in between the air raids, acting almost as if they don’t believe it’s ever going to happen to them.

The incendiary bombs inevitably fall and devastate the city, destroying half the town and killing 100 000 people in a night. The bombs were specific, particular to the needs of the location objectives: Japanese cities at the time were comprised of buildings made predominantly of wood. There was no need to blow them up with high explosives, all they needed was to trigger a few thousand of these which would result in a sea of fire. It was very effective, to say the least.

Unfortunately for our protagonists, the bombing results in their mother dying an apparently excruciating death a few days after the bombing. Whilst the design of the shots is not overly ‘realistic’, as in trying to explicitly replicate scenes as they would appear in real life, many details are included, details you wouldn’t ordinarily expect in animation of this nature. There is no shying away from these issues, which stands in the film’s favour.

Seita and Setsuko, motherless now with their father off fighting in the navy, are at the mercy of the elements and the goodwill of others, neither of which can be depended upon for two long. After a short stay with a nasty bitch of an aunt who resents having to look after them in a time of food rationing and poverty, they decide to go it alone in the wilderness.

Their fate is sealed at film’s beginning, we know what is going to happen to both of them throughout the course of the film but not why. As the film gently follows its course to the inevitable we are privy to the moments of desperation, scrounging, scrambling for survival, but also moments of joy, humour and transcendent beauty. They find a refuge in a hillside looking onto a lake as they clearly haven’t the faintest idea of how they are going to survive despite having a kickass view.

Here the artwork becomes a moving Expressionist painting come to life. Since the film is in no rush to get to its heartbreaking destination, it meanders over the minutia of their lives. There is such incredible attention to detail in these latter sequences, in terms of the little things the characters do for each other, that I found it utterly captivating. The focus on the fireflies, the tin of fruit drops, filling the tin afterwards with water in order to get the last bits of sugar out for Seita’s sake, all these details combine to encompass a truly masterful work.

And so it goes, until we find our characters in a different state, looking down upon a new Tokyo, long after the war has ended. The bittersweet ending perfectly matches the tone and elegiac feeling of the story.

Sifting through the additional extras on the DVDs later on I found that there were levels to the film that I hadn’t even considered. The director openly states that his intention was to make the older boy Setsuko the ‘villain’, so to speak, of the piece, representing their fates as ultimately his fault because of his laziness and selfishness (!) I find this staggering, because whilst I questioned in my mind some of the character’s actions in the film, I never gleaned the fact that the director had such an objective in mind. He saw it as a comment on contemporary Japanese youth, whom he also sees as lazy and selfish.

He expresses, not without irony, how disappointed he was when audiences sympathised with Setsuko and Seita so completely that they didn’t have judgement left to mete out. It is a beautiful example of where a work of art escapes the confines that its creator(s) originally envisage, expanding and growing in ways unexpected.

Another factor brought up by the supplementary materials which I didn’t know was the fact that the story itself was based on the real life experiences of the author during World War II, and that he basically lived the life of Setsuko, having to watch his younger sister die of starvation. Obviously his life did not end in the same manner, but his guilt comes through, painfully and honestly, in the details which make it look like he himself, and not the war, was responsible for his sister’s death. This adds additional elements to how one reads the ‘text’ of the film, giving it even more depth and complexity than I expected.

As if the story needed to get any sadder! Jeez Louise, I’m making it sound like a 5 hanky weepy for the Steel Magnolias / Dying Young chick flick crowd, and it is most certainly not. As always I am mindful of the fact that some might watch it and be unmoved, or that some wouldn’t be interested in wasting two hours of their lives watching Japanimation of such depth (and such glacial pacing, one must admit). To quote Mr T from The A Team, ‘I pity the fools.”

8 times out of 10 the pity of war is never realised until too late.

"No matter how far you roam / There's no place like home." - Grave of the Fireflies

- 3757 reads